I planned a recent walk to take-in two churches. The first church I wanted to visit was St George’s Tron – on Buchanan Street/Nelson Mandela Place – and the second was St Vincent Street Church, and which was – up until very recently I believe – home to the congregation of the Glasgow City Free Church. I’m only going to talk about my encounter with the first of these in this post.

I began my walk on Queen Street, and aimed to head to St George’s Tron from there, heading out of the western exit of Royal Exchange Square and up Buchanan Street to Nelson Mandela Place. Queen Street was my starting point because – on a previous walk – St George’s Tron had crept into my awareness, despite it being a block or so away. On that walk, I’d developed a claustrophobic sense of a Presbyterian topology hemming me in, as – triggered by the landscape – my earliest memories of Glasgow’s city centre revealed themselves as significantly shaped by that religious undertow. St George’s Tron was the first church I attended in Glasgow, and is not far from my old student halls, where I’d hoped to make a break from certain religious aspects of my upbringing. And so I wanted to walk to St George’s Tron itself, to see what a more direct encounter with it might hold for my personal and religious imaginings of the city centre.

However, what I had not taken into consideration was that the day on which I’d planned to do this walk fell in the middle of Glasgow’s hosting of COP26, which significantly shaped how I was feeling as I navigated the city, even before I began my planned drift. As I took the subway from Kelvinhall to St Enoch, every station was jumping with activists, making their way to join the youth march. Noticing the marchers heightened a jumble of feelings that had been swirling within me all week; a sense of joy-in-unity mixed with sadness at the uncertainty and peril of the climate crisis. Quickly looking up the route of the march once I was above ground again, I realised that I could get between the two churches that I wanted to visit by walking part of the march in reverse, along West George Street and down Pitt Street. It occurred to me immediately that this was the route that I should take (I’ll talk about this bit of my walk in a further post).

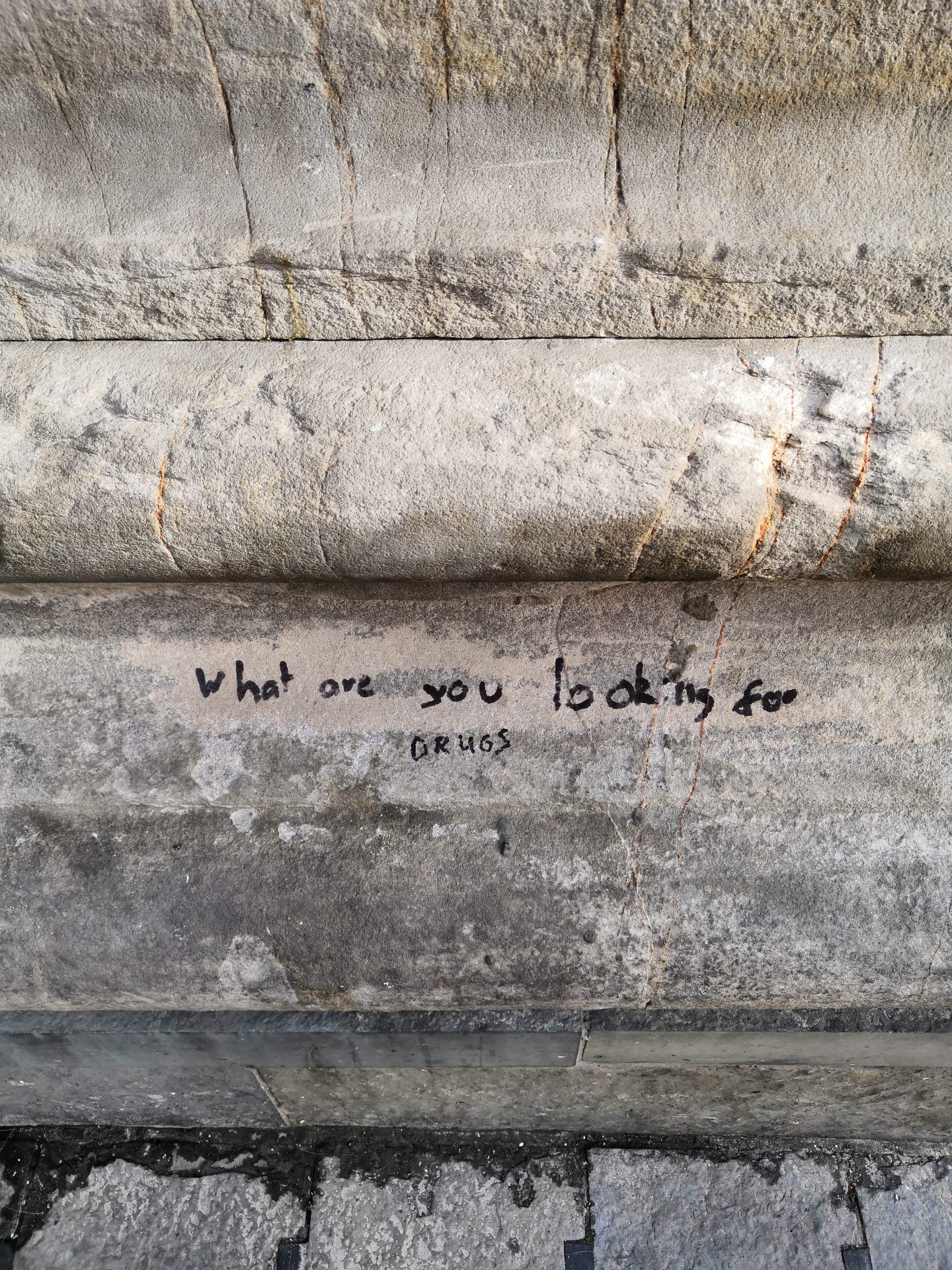

As I walked from Queen Street through Royal Exchange Square, I was enticed into walking a circuit around the Gallery of Modern Art – formerly the Cunninghame Mansion – in order to peer down the lanes that exit Royal Exchange Square into some of Glasgow’s back streets. However, the walk took an unexpected turn when I noticed a different kind of ‘exhibition’ at the GoMA. On my last walk on Queen Street, I had photographed a couple of bits of graffiti, scrawled, mostly in what I’m assuming is felt-tip pen on the GoMA’s steps. This time, I scoured the whole of the GoMA’s portico. I was lured into this diversion by another couple of cheeky sketches, but quickly realised that the veranda is covered in graffiti: innuendos, manga, Instagram handles, song lyrics, drug references, stickers, cartoons of ghosts, and what looks like the odd paint drip. Royal Exchange Square has been a hang-out for goth kids and skaters for a number of years, and their portico scrawls have a deliciously grotesque charge. They not only conjoin the ‘high culture’ of the neoclassical architecture with the ‘low culture’ of teenage graffiti, but express an irrepressible impishness, gleefully and illegally daubed on the poised architecture, that – however unconsciously – mocks its supposedly refined, ill-gotten ‘dignity’.

Soul searching…

Haunting…

Walking out of the square’s western exit at Royal Bank Place, I felt a vague dread that I often feel on Buchanan Street. The trepidation I felt at approaching St George’s Tron intensified, sloshing around in the pit of my stomach as I glanced up North Court Lane, along which I used to drag cans of used cooking oil. Those cans of cooking oil are a more recent memory, but the sense of dread on Buchanan Street is older. I’ve often found it an anxiety-inducing space, at least from around Donald Dewar’s statue down to Princes Square; there’s something unforgiving about it. That’s not to say that this is an essential quality of Buchanan Street – placed emotions are always compound, networked, subjective, and fluid – but surely it’s intensely consumerist (even rat-race-like) vibes must give many others similar chills.

However, as I approached St George’s Tron, rather than intensifying – as I had anticipated – this dread actually began to lift. The church was covered in eight floor-to-ceiling banners designed by the Christian development agency, Tearfund, and Glasgow-based artist, Coll Hamilton. In addition to these, other notices on the outside of the church welcomed people in to pray throughout most of the day during COP26. But upon looking into the church, it was clear there was much more than just praying going on. Entering the church, it became apparent that the sanctuary had been given over to faith-based climate activists and that a variety of meetings were happening. Snippets of conversation I overheard all had a political-organisational tone.

The sense of levity (even joy) I felt in seeing the church set up like this was partly shaped by what I’d been thinking of on earlier parts of my walk, and partly in response to some of the controversies that I was aware had been circulating around St George’s Tron’s former congregation during COP26.

Oil can alley…

SGT

Earlier in the walk – before I’d even got to my planned starting point on Queen Street – I popped into the St Enoch Centre to make a few notes on my brief commute. Whilst sitting in the food court of the mall, I became oddly transfixed by the cartoonish plastic bins made in the shapes of animals: big green frog, dolphin, happy bear. Part of this fascination was to do with the fact that I remember these kinds of bins from my own childhood, and – as far as I can remember – their form has barely changed. But I was also drawn to them because they seemed to represent a kind of libidinal engineering, symbolically linking cartoon entertainment and cuddly representations of nature with a desire to maintain communal space. And so from this point on in my walk, thoughts about cultural interventions that develop desires for the communal (or desires that are conducive to the communal) and the popularisation of seemingly ‘fringe’ or ‘unfashionable’ desires via culture, kept ringing around in my head.

Palpably libidinal…

Therefore, upon reaching St George’s Tron, the evidence of its handover to climate activists lifted my spirits, because I wondered whether (even hoped that) this scene represented the popularisation of – what might have once been – fringe or unfashionable ideas within the Church of Scotland. This sense (or hope) of change is related to my personal experience of seeing this church change over time – in both its presentation and congregants – and my knowledge of how its former congregation and leadership is perceived in wider networks of Christians in Glasgow. St George’s Tron made headlines in 2012 when the congregation left the building in Nelson Mandela Place after splitting from the Church of Scotland over their acceptance of ministers in same-sex relationships. This decision was taken, in part, due to the preference for a ‘reformed theology’ – an evangelical theology which rejects knowledge of God other than through (a particular) reading of the Bible – within the leadership of what is now a multi-site congregation know simply as ‘The Tron Church’. The Tron’s way of embodying this reformed theology caused controversy once again during COP26 when they hung a banner outside one of their locations that read: ‘The world’s most urgent need is churches preaching Christ crucified – not climate change’. The fact that this trolling-type behaviour was no longer visible at St George’s Tron – one of the Church of Scotland’s most prominent sites, and a key site in my own perception of the Kirk – and had been replaced with a congregation that seemed to endorse solidarity with the vulnerable, regardless of their theological position, seemed to me not only to underscore the Church’s desire to be more broadly popular (as ‘the reformers’ would claim), but processes that have changed what is popular within the Church. This was sense was accentuated by conversations I had with friends who were still part of the wider Church in Glasgow, and who found The Tron’s COP26 banner objectionable, affirming the new congregation at St George’s Tron’s proactive engagement with the climate crisis.

In addition to the immediate sense/hope of the Church’s changing vogue on my walk; later – whilst I wrote up some notes and reflected a bit more on what was and is popular within the Church – I was struck by an eerie (but excited) sense that my own rejection of reformed theology might have been less to do with my own rational jettisoning of Calvinism, and more to do with the work of organisations like Tearfund and other grassroots justice organisations within Church. Part of the reason I left the reformed church (before leaving the Church more generally) was a persistent sense that many expressions of it that I encountered placed insufficient priority on social justice (or supported social justice in bad faith). But the reason that I had become increasingly uncomfortable about this sidelining of social justice was because of the ways in which the demand for social justice haunted almost all of my experiences of Christianity; indeed, I might argue, it has perpetually haunted Christianity, as a theology and set of social relations, more generally. Biblical narratives (rich man, camel, eye of needle etc) and social-justice practices have always permeated the Church at every level. The sense for in/justice that was aroused in my own engagements with the Church (and surely must be in the experiences of many others) has not shifted, and it ultimately – for the time being anyway – won-out out against my desire to stay in the Church. (There are many other reasons I left the Church, not all of which are so ‘right on’. Nevertheless, some sort of commitment to justice remains; my tithe does not). So the transformation of St George’s Tron that my walk confronted me with raised an exciting question: might the narratives and organisations that haunt the Church more generally – but here, the Church of Scotland specifically – with the demand for social justice, have worked their way towards some sort of popular recognition (even celebration)? This is an open question (which includes the possibility that meaningful commitment to social justice is not as popular within the Church as might be hoped, and that even if it is popular – matters of implementation and politics are still fraught), but the symbolic transformation of the St George’s Tron from an enclave for ‘reformed’ cranks to a climate activist hub prompted me to consider that it might be worth asking.

New standard…

Blue police lights flash around the sanctuary. The youth march is passing. There’s an excited rush of people from the sanctuary towards porch windows and the street. Those from within the church smile, clap, cheer, and take photos, as one of the most inspiring demos that I’ve ever seen moves past. Despite the incredibly wide range of demands represented on marchers’ banners and bits of cardboard, the sense of unity is, again, palpable. The Church sits in the middle of it for a while, adding something.

As I carried on my walk and headed up West George Street, I bumped into a Quaker activist, who was visiting from London, and had been using the Meeting House I now attend as a base. When I enquired as to what they’d been up to, they told me that they had been spending the week developing networks within churches and interfaith groups. They worked less with institutions and more with grassroots activists, trying to make an impact on loss and damage finance but also working on a moral framing for this that will be popular in various faith circles. Maybe they’re succeeding…